With thanks to my friend and inclusive TOD co-conspirator, Gerhard Hitge.

In Oct 2018 I wrote “There’s a rail Day Zero, what can you do about it?” Since then, the Central Line in Cape Town stopped operating all together - we really did hit that ‘day zero’. For commuters from Khayelitsha, things got even worse - the MyCiti bus services also stopped running - leaving them with only Golden Arrow buses and minibus taxis to choose from. For many households, this is having a huge and prolonged impact - on monthly finances, personal safety, hours at home, and employment. They were captive to rail, and now they are captive to their neighbourhood, or captive to debt, long hours in traffic and favours to caregivers. UniteBehind is an organisation that has aimed to give a voice to these stories, and hold to account those responsible.

I’ve been a long-time user of public transport. Towards the tipping point of the decline I was using the train to get to Paarl. When it works, it works hey. It can even be a pleasure - going past suburbs and then even past a lion park! But when it doesn’t work and it’s dark and you’re one of very few people left on the train (or far too many), it’s… it’s not lekker. During lockdown, the trains stopped running for PRASA to do the long-awaited modernisation works (more on that below), and I made the move to Paarl - but still needed to get to town every now and then. I’m one of the privileged few - a “rail chooser” - who could upgrade to a car - so I did, albeit with great reluctance and disinterest - and I named it Lucky. After you know who. But I’m adamant that when I can take the trains again, Lucky will get sold.

PRASA publish their various corporate strategies and plans online, and Raymond Maseko is making an effort to be visibly accountable for actions the PRASA group is taking towards implementing these plans in the Western Cape.

I took a look at PRASA’s latest plans (2021/24) and I try to follow what is said by and about PRASA, and I do my own spot checks as a concerned commuter (you still haven’t fixed the cables at Stellenbosch, and don’t get me started on the apocalypse that is Pentech). However, observing their step by step approach to modernisation, and progress on the Southern Line, and first rings of the northern and central lines, I’m cautiously optimistic, and have some ideas of how things could be sped up.

1. Stabilise the basics, amplify with partners

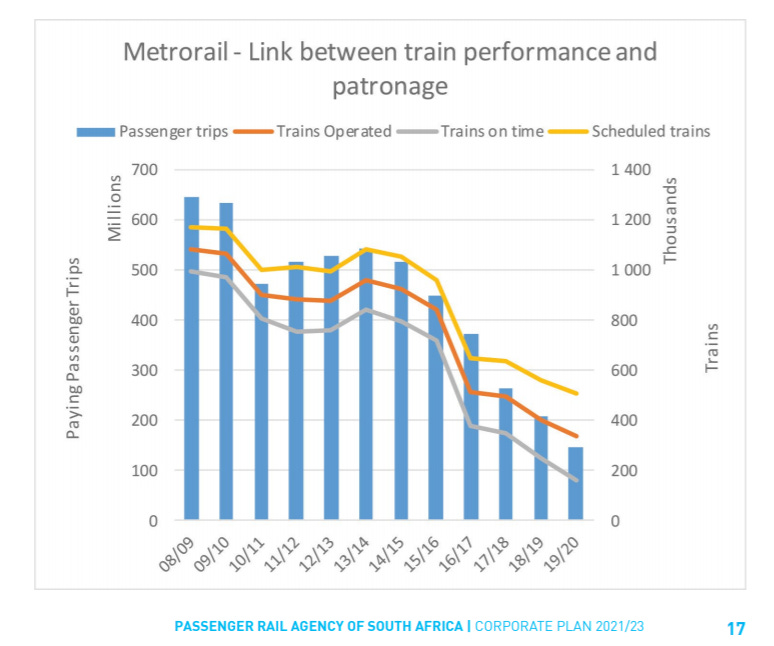

PRASA’s corporate plans recognise that they have to focus on fixing things, and getting the basics back in place. A lot of infrastructure and stock has been lost, and there are big challenges with land occupations, ongoing threats to the safety of infrastructure and staff, and stabilising the operational and governance matters of the PRASA family.

While ten to fifteen years ago, PRASA had huge ambitions with new rail connections and land development programmes, these have been toned down to focus on only those that were very far advanced in planning (i.e. well past design and into procurement phases). The majority of PRASA’s resources (leadership capacity, technical know-how, and financial resources) need to go towards just getting services running again - not new projects (as sad as that is for city-makers like me).

Amplify through partnering

However - more can be done by recognising other actors in City-making, or potentially investigating rail-licensing models.

The City of Cape Town, for example, has been pushing its densification policy and there has been take-up of rights along the Southern Line especially. Covid has of course had an impact on mobility patterns overall, but densification along that route could increase overall user numbers with a) appropriate messaging and scheduling and b) good urban management and safety from the role players (mostly CIDs along this line) managing the spaces between the buildings where people live, and the stations where they will travel from.

Where PRASA owns land, not every station-precinct development needs to be designed-and-developed by PRASA-CRES. These can be done in SMART-partnerships with developers, including Social Housing Institutions, from earlier in the development planning cycle. In this way. station precincts that have been on the list for development for two decades, need not be delayed further.

By working with these partners, much of the Southern Line could be taken care of - leaving PRASA to focus its energy’s where they are arguably most needed: the Central and Northern Lines.

Additionally, there are legislated roles. I wrote in my original post about the Intermodal Planning Committee and Land Transport Advisory Board. These structures have historically played important roles in coordinating the actions of several role players in transport and related land use planning and their performance and strength of relationships should be of concern to the general public.

Finally, new models for integrated land and rail corridor development can be explored.

In Cape Town, the primary new line that has been in planning is the Blue Downs Rail Corridor: a rail reserve exists to connect Bellville to Khayelitsha, via Kuilsriver and connecting a Nolungile.

ACSA have purchased the Swartklip (former Denel) site at Nolungile, which would be catalysed by this strategic line that would connect the northern suburbs to the metro-south east of Cape Town. The development of that site could have benefits to the communities of both Khayelitsha and Mitchells Plain. Along the rail route there are further land parcels, and three new stations, each viable for private sector middle income development and mixed-use commercial development.

This is an opportunity for a new subsidiary to be created (perhaps jointly with ACSA), or a rail-license to be put out to tender. The National government have indicated their appetite for new models in recent moves with SAA, SABC, the Ports Authority. This is an opportunity waiting to be packaged - without asking anyone to buy the current “mess”. Packaging needs to enable risk sharing between the private and public sector, and translate public value creation goals of “sustainability”, “affordability”, “inclusion”, etc. into tangible metrics to avoid gross exploitation of the opportunity.

Fun fact: The Cape Railways built in the 1860s were originally run on a private operator licencing model. There were originally two company’s - the Wellington line, and the Wynberg line. The operators couldn’t reach agreement about sharing a line from Salt River - where the lines met - into town; and so until today we still have multiple lines coming into town from Salt River. If the Blue Downs line were to be operated by a new operator, let’s try stick to the original designs where the lines do merge at Kuilsriver and Nolungile.

2. Build back Modern, radically

PRASAs modernisation plans were conceptualised in the 00s, so it’s about time they’re being implemented. But they actually are - so, we are “back on track”, so to speak. These plans include upgrading stations and critical infrastructure such as signaling (the things that tell the trains when to pass, when to stop, etc.), rolling stock (the nicer looking blue trains we are starting to see) and other infrastructure that allows for new fleet, communications among staff, and information to commuters - in other words, this is the enabling work for improvements to the entire commuter experience.

A recent newspaper article laments progress with these plans - it’s a bit like kick-starting a big, complex engine - but as you have one part fixed, the oil has been taken, or the fuel pipe disconnected, and so on. Where do you start? And how do you hold all the pieces together at once? At yesterday’s #SATC2021, PRASA CEO Zolani Matthew reportedly said "It is no use putting billions of rands in the system. If we can't protect the system or the people." PRASA’s safety plans include security at stations, CCTV along lines, building walls in areas they battle to secure, partnerships with local authorities, SAPS, intelligence units, and communities. Securing infrastructure that is not yet in use, securing it once it is in use, and securing people are all discreet operations.

Additionally, if you start with one line, perhaps there will be a problem with social legitimacy on that choice, and protest or other action taken. If you start with investment across the whole network, but you aren’t yet running it, there are costs, but no revenue. Each choice not only has a set of financial costs and benefits, in a not necessarily linear sequence, but also stimulates political and social responses relating to the transport and land system.

It’s a Hirshmanian moment

Hirshman wrote in Strategy that there is “one basic scarcity” in development - and that is the ability to make decisions. We certainly experience a lot of this in South Africa - frozen by the complexity of our challenges, and the fear of getting it wrong - especially when trying to clean up organisations or run clean organisations - we are hyper-accountable to auditors and probity processes and not accountable to outcomes, with little to no incentive to improvise, innovate or show hope.

The state of our rail infrastructure and the complexity of the task necessitates that recovery will be unbalanced. PRASA has set in place sequences which broadly make engineering sense, but will need to be tolerant of some disorder - they will have to be observant of where additional investment is needed, as those areas emerge as much as where they were planned, and have the leadership capability to take those decisions.

3. Keep in touch with your commuters

There’s a lot of technical advice to be offered right now. Fresh perspectives, and sobering global expertise has its place. These should be seen as complementary to the stalwarts of the South African rail system who have tacit knowledge of its technical idiosyncrasies, and perhaps more especially of our commuter needs and profiles.

I’ve recently heard sweeping statements like “everyone is working from home” - out of touch with the manufacturing economy that still shapes many South African metros and working and informal class commuter profile, or the semi-regional commuter, and ignoring mobility data that shows South Africans are very much on the move. Another was “everyone who used the train now takes Uber” - clearly out of touch with the spatial and financial realities of the average public transit user.

When I worked on the feasibility study to drop the railway lines one of PRASA’s conditions was that there should always be a full service offering to commuters all the way into town - even if that meant offering PRASA-bus services. That there should never, ever be disruption to service that would see passengers move to other service providers, or risk losing their jobs or adapting their lives in other ways. We were only looking at the stretch from Woodstock into town, and only just over a decade ago.

PRASA needs to bring back that absolute commuter-centric focus. Deliver a service to your customers, no matter what it takes, to get them reliably and safely from A to B, until the whole network is operating fully again. We might find that in these solutions, are the thin ends of the wedges towards modal, ticketing and fare integration.

I’ve recently read Jose Burman’s “Early Railways at the Cape” and was struck by how some things are always the same - the first time a train seat was slashed was just weeks after the first night service was opened in 1866, the culprit a Diocesan (Bischops) college master. The charges were dropped when the school principal offered to pay the expenses. The early railway company’s faced competition from the minibus-predecessors, the “omnibus”, whose drivers called vocally for passengers as they drove along and had more freedom of where and when to stop. The early railways faced infrastructure vandalism and sabotage (violent sagas at Bennetsville (now Klapmuts), disruption at Salt River and others seem long forgotten - what we remember is that it was overcome.

Below: A derailed engine during the navvie “war” at Salt River, 1861, South African Railways, Jose Burman, Early Railways at the Cape